What is a Tea Processing Chart?

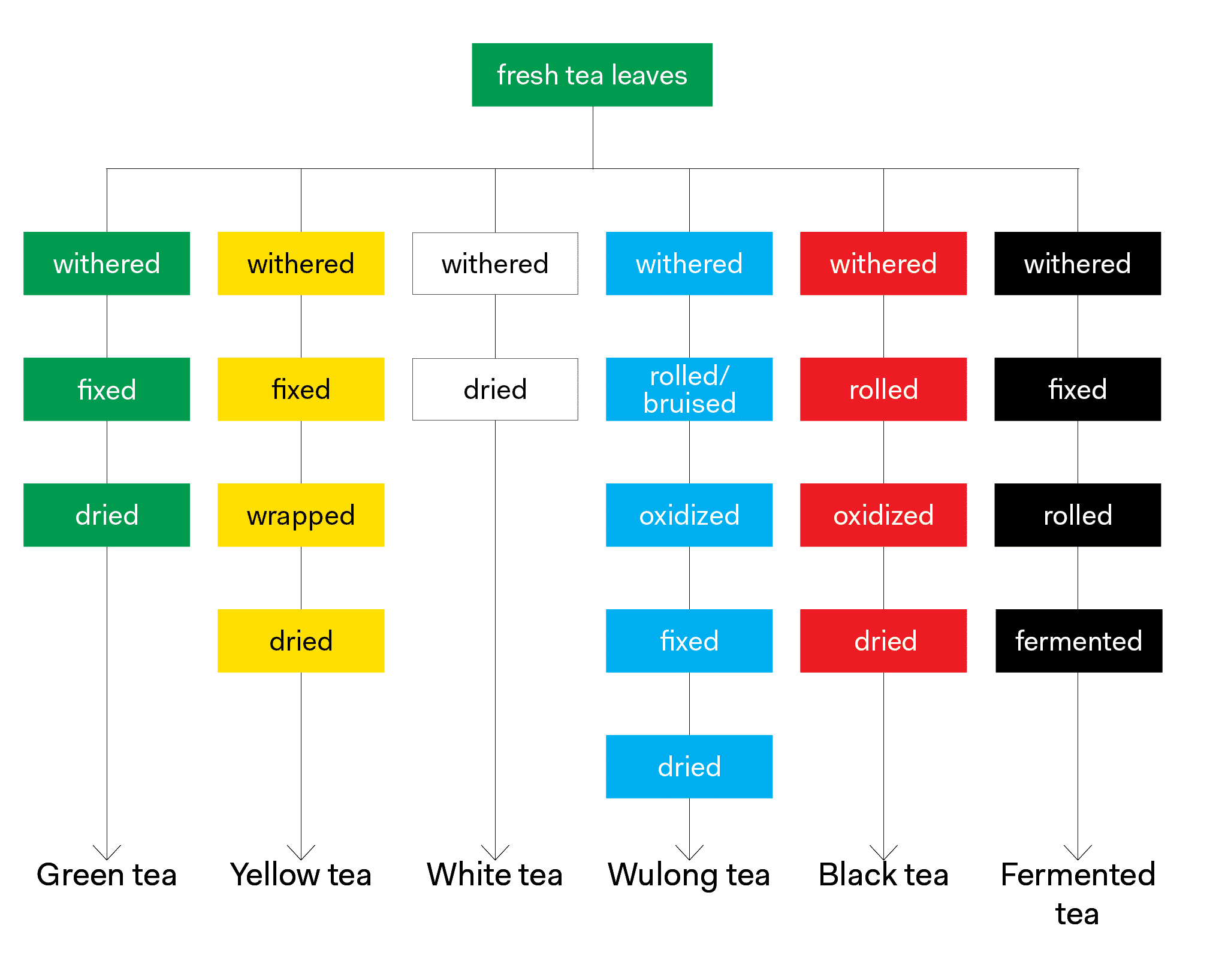

What is a tea processing chart? A tea processing chart refers to a chart that shows the processing steps that different tea types go through after being plucked and before they reach your cup as a means of tea classification.

Tea processing charts have been essential items in the toolbelt of tea educators for years. However, nearly every processing chart that exists today excludes many styles of tea and sometimes entire types of tea. I posted the first version of my tea processing chart in 2013. Since then, I have made countless edits to it in an effort to create an easily understandable tool for tea education. Early on, I adopted a lumper mentality.

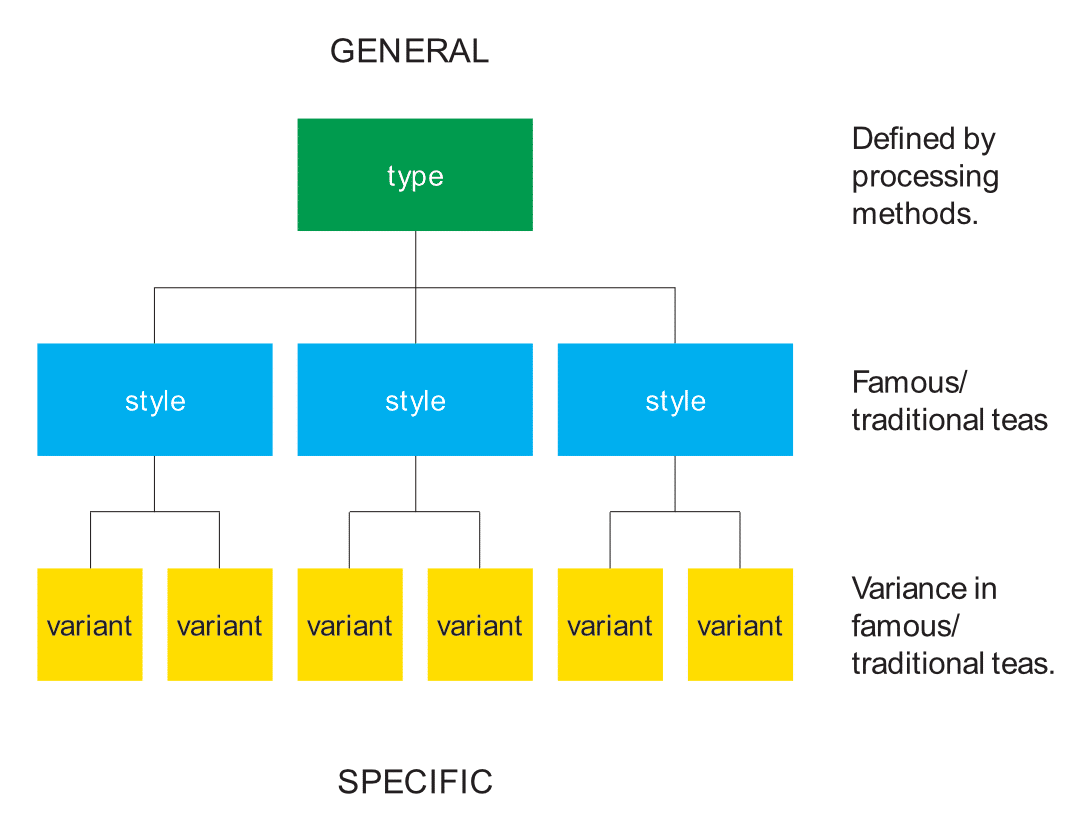

In any discipline that requires placing things into categories, there are generalists and specialists. These two factions are often referred to as lumpers and splitters. In general, lumpers prioritize similarities over differences and splitters prioritize differences over similarities. Tea snobs are inherently splitters; always pointing out differences in things in order to make themselves feel smarter than the average person. Splitters love to say things like “it’s more complicated than this!” or “there are no absolutes in tea!” And while they may be right, I don’t believe that the splitter mindset has any place in beginner’s tea education.

A major turning point in my tea study was when I stopped trying to create a chart outlining all of the steps that each tea type goes through and began to evolve the chart so that it only exhibited the minimum steps required to be considered a tea of a specific type. This simple change in thinking led to the processing chart in it’s current form.

What follows is an exploration of the challenges that exist when classifying the diverse world of tea and ultimately, what led to the current thinking exhibited in the latest processing chart. But first, some groundwork… we will be working with seven main categories of tea, each defined by the unique processing steps they go through: green tea, yellow tea, white tea, oolong tea, black tea, fermented tea and altered tea.

It may help to read my post A New Look at Tea Classification so that you better understand the terms used in this post before continuing. And finally, this post is really nerdy, so I apologize in advance!

Green Tea

In one simple sentence, green tea is a type of tea made from leaves that have been withered, fixed and dried. There’s no controversy surrounding the fact that leaves destined to be green tea are heated (via a processing step called fixing) and thus are not allowed to oxidize. It is this prevention of oxidation defines green tea. However, the amount of withering that occurs before the leaves are fixed has led to a lot of confusion in the tea world.

There is a notion that tea leaves destined for green tea production are plucked and rushed to the processing facility to be fixed, while this is likely the case when steamed greens are being produced, it isn’t the case for most pan-fired green teas. Leaves that will be pan-fired go through a distinct withering step to prepare them for further processing.

Regardless of the style of green tea being produced, the leaves are allowed to wither and are flaccid once they reach the pan or the steaming machine. Whether or not the producer considers withering a processing step or intentionally withers the tea leaves before fixing them is another matter altogether and the heart of the confusion surrounding withering in green tea production.

Yellow Tea

Yellow tea is defined by a processing step known in Chinese as Men Huang (闷黄). Translated, this means xi. During men huang, small portions of fixed tea leaves are wrapped into bundles either using paper or cloth. While wrapped, the leaves slowly change color from green to yellow-green as chlorophylls are broken down, the vegetal flavors within the leaves begin to mellow and the leaves partially oxidize.

The trouble with yellow tea production today, is that some yellow tea producers are skipping this defining men huang processing step altogether, essentially selling a green tea as a yellow tea. This practice is common among Huoshan Huangya producers in China’s Anhui province.

Another fun yellow tea classification issue arises with a tea from South Korea called “Hwang Cha” which translates directly to Yellow Tea. Turns out that this tea is nothing like yellow tea at all in the Chinese sense. South Korean Hwang Cha is produced by withering tea leaves, they then go through a men huang process and are then dried. Because of the lack of a fixing step here, oxidation is able to run it’s course during men huang and the resulting tea is more of a highly oxidized oolong or black tea in nature. In South Korea, it is classified as a balhyocha (발효차), which translates to “fermented tea” but really refers to “oxidized tea.”

White Tea

Many consider white tea to be unoxidized due to the fact that raw material destined to be white tea doesn’t go through a processing step labeled oxidation. However, it is during a long withering period, sometimes lasting several days that the leaves slowly oxidize.

The oxidation that occurs in white tea production is minimal, but it can not go unmentioned. Another thing that many tea companies get wrong when defining white tea is the fact that white tea is not always made up of buds. Bai Mu Dan, and it’s lower grade variants, Gong Mei and Shou Mei are made up of buds and leaves. White tea production is not only limited to China’s Fujian province either, it is now being produced in small quantities in Sri Lanka, India, and Nepal.

Wulong Tea

Wulong refers to semi-oxidized tea. But semi-oxidized is a term that needs some unpacking. Regardless of the style of wulong being produced, processing begins with withering. From here we experience some variance where the initiation and control of oxidation is concerned. Traditional half-ball shape oolongs like those from China’s Fujian Province and Taiwan are either shaken or tumbled, a process known as Yao Qing (摇青) literally, rocking the green. The goal here is to gently bruise the edges of the leaves, initiating oxidation.

Some teas coming out of India and Nepal labeled oolong do not go through this process, rather, they are rolled using an orthodox rolling table. The wulong nature of these teas comes from the prevention of oxidation, much of the process resembles black tea production, but the leaves are dried before reaching a normal black tea level of oxidation resulting in a semi-oxidized tea. Some tea experts hold that these styles of tea do not deserve the wulong designation.

Rolling is another important step in producing half-ball style wulongs as in Anxi and Taiwan. Here, the leaves go through an iterative process called cloth-wrapped kneading where bundles of leaves are wrapped in cloth then kneaded. The wrapped ball of leaves is then broken apart, then re-wrapped and the process begins again. This is an iterative process that is performed many times.

First Flush Darjeeling teas are also a source of confusion as they are typically only lightly oxidized to exemplify the first harvest of year. Because of their semi-oxidized nature, many tea experts consider them to be wulong, though they are often marketed as black teas. Some even refer to First Flush Darjeeling tea as lightly oxidized black tea which of course is an oxymoron because the defining characteristic of black teas is that the leaves are fully-oxidized during production.

Thus, in order to handle all semi-oxidized teas in a processing chart, I refer to the initiation of oxidation as “rolled/bruised” and I’ve omitted the cloth-wrapped kneading step because while that is a defining characteristic of several teas on the style level, it is not a defining characteristic of the wulong type itself.

Black Tea

Black teas are often described as fully oxidized teas. To be more accurate, let’s say mostly oxidized as it’s chemically impossible to fully oxidize tea leaves without first grinding them into a fine powder. The basic process for making black tea from fresh tea leaves is: withering, rolling, oxidation, and drying. The goal of black tea production is to induce and control oxidation until the tea leaves achieve a prescribed level of oxidation.

There isn’t much confusion with this type of tea, black tea production is quite straightforward as it is the most produced tea type in the world. It is important however, to note that what most of the world outside of East Asia refers to as black tea is known to the Chinese (and most Asian countries) as red tea (红茶, hong cha).

Calling this tea type black tea is confusing because the Chinese already have a tea category called Hei Cha (黑茶) which translates to black/dark tea.

Calling this tea type red tea is also confusing because most of the western world uses the term red tea for African Rooibos, which isn’t tea at all but rather a tisane from leaves from the Aspalathus linearis bush. That’s fun, right?

Some confusion may arise when teas that are not close to being fully oxidized are marketed as black teas. In fact, I was sold a lightly-oxidized black tea while traveling in China in 2015.

There are two schools of thought here when encountering these semi-oxidized “black teas,” the first is that if the tea was produced without any sort of Ya Qing (see Wulong above) process, then it cannot possibly be considered a wulong, and the tea is oxidized much more than a traditional wulong, so it must be a black tea! The second school of thought would say that the producer’s intention was to create a black tea and the production techniques resemble black tea production, so it must be a black tea! There truly is not a wrong or right answer here.

Fermented Tea

Fermentation in tea production refers to the breakdown of substances by bacteria, yeasts or other microorganisms. Fermented tea, a source of so much confusion in the West. I call this category fermented tea because it includes heicha, puer, and several fermented Japanese teas. If I were only referring to fermented teas from China, I would call this category, heicha. Yes, heicha.

Puer is not the “6th tea category” yet I see tea books and classification charts with no mention of heicha whatsoever. Puer-heads typically shake their fist at me when I say this, but take a look at the processing steps that I list for the production of fermented tea: withered, fixed, rolled, fermented. You may notice the omission of several processing steps sometimes associated with these styles of tea, drying, compression, etc.

I dramatically simplified the processing chart so that all fermented teas fit into it. Drying had to go because the drying step occurs before fermentation for Shu Puer production and after fermentation for most Heicha production. What’s left are processing steps that define fermented tea, all of it.

Let’s talk about Puer, specifically Sheng puer, this tea is more like a green tea in production, but the intent (at least today) is to age this tea which refers to a combination of slow oxidation and fermentation over time. In my unscientific opinion, the aging of sheng puer is more oxidation than fermentation, but fermentation does occur and therefore this is considered a fermented tea.

The method of fermentation differs from style to style, Shu Puer and Heicha both go through a wo dui / piling step (and some consider Shu Puer to be part of the Heicha category). Sheng’s fermentation happens during the aforementioned aging.

Altered Teas

Any tea type above can be altered. Altered teas refer to teas that go through additional processing steps during or after primary processing before being sold. This can refer to flavoring, scenting, blending, smoking, aging, decaffeinating and grinding. The majority of teas sold in the United States are altered in some way.

This post is part of a series on tea classification, if you are new to tea, start with A New Look at Tea Classification. This post explains the background of and thought that went into A New Look at Tea Classification. Or if you are are already well-versed in tea classification, you can skip right to the final tea processing chart.