What is Oxidation?

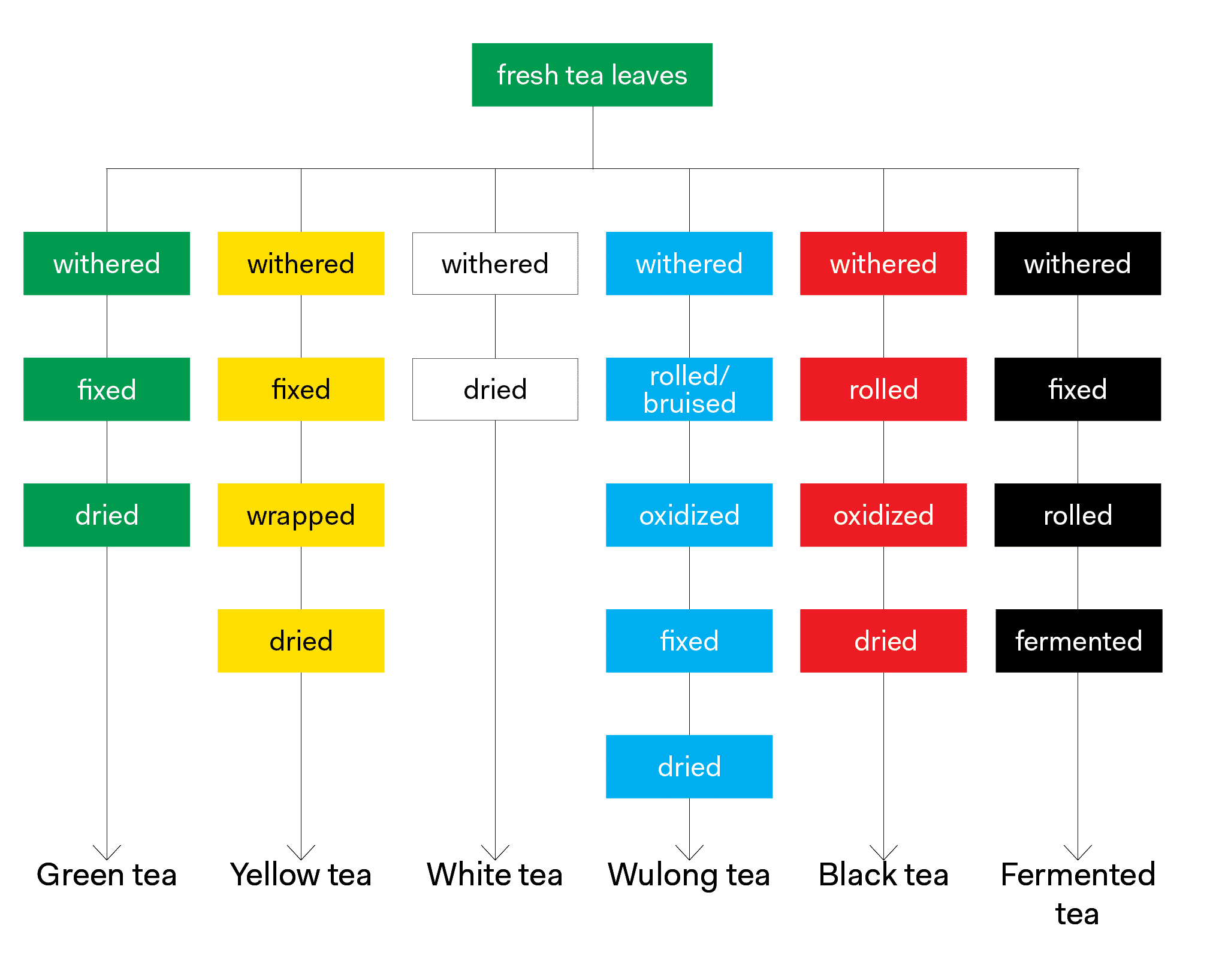

Oxidation refers to a series of chemical reactions that result in the browning of tea leaves and the production of flavor and aroma compounds in finished teas. Depending on the type of tea being made, oxidation is either prevented altogether or deliberately initiated, controlled and then stopped.

Much of the oxidation process revolves around polyphenols, particularly the enzymes polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase. When the cells inside tea leaves are damaged and the components inside mix and are exposed to oxygen,1 a chemical reaction begins. This reaction converts the polyphenols known as catechins into flavanoids called theaflavins and thearubigins (which are also polyphenols).

Theaflavins provide tea with its briskness and bright taste as well as its yellow color,2 and thearubigins provide tea with depth, body and its reddish color.3 Chlorophylls are converted to pheophytins and pheophorbides (pigments that lend to the black/brown color of dry oxidized tea leaves) during oxidation, and lipids, amino acids and carotenoids degrade to produce some of tea’s flavor and aroma compounds. Tea producers use special methods to initiate, halt (fix), or even prevent oxidation in order to produce different flavors in a finished tea.

Initiation of Oxidation

Oxidation begins when the cell walls within tea leaves are damaged. To achieve cell damage, tea producers macerate, roll or tumble tea leaves to intentionally initiate oxidation. Maceration is the quickest path to full oxidation because the insides of the leaves are immediately exposed to oxygen, resulting in a greater mixture of the chemicals within.

Maceration is typically used in mass production methods to create CTC (cut tear curl) tea or other broken leaf teas. The process is achieved using a rotorvane or a CTC machine. Rolling results in a much slower and gentler oxidation, and it is usually done using a rolling table or by hand.

Tumbling is an even gentler way to initiate oxidation, and it is achieved using large cylinders wherein the leaves are tumbled or by hand-shaking the leaves on top of a shallow bamboo basket. Regardless of the method of initiation, great care must be taken up to this point as any damage to the leaves before processing will cause premature oxidation and result in an unevenly processed finished tea.

Control of Oxidation

Control over oxidation is maintained by introducing warm, moist, oxygen-rich air over time. The extent to which oxidation is allowed to occur has an astounding effect on the finished tea. Oxidation occurs best between 80–85°F and is slowed nearly to a halt at 140–150°F.4 Thus, when the tea producer wishes to halt oxidation, they heat the leaves. This heating process is known as fixing.

Fixing or Halting Oxidation

Fixing works by denaturing polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase – the enzymes primarily responsible for oxidation using heat. Fixing is also commonly referred to as de-enzyming,5 denaturing or kill-green.

The term kill-green is derived from the Chinese term shaqing (杀青), which translates to killing the green. The tea leaves must be heated to approximately 150 degrees Fahrenheit to “halt” oxidation. Oxidation is further slowed by drying the leaves, but it never completely stops. At temperatures over 150 degrees Fahrenheit, oxidation continues to occur at an extremely slow pace.

The process of fixing requires precise control of the temperature and length of heating; each has to be adjusted depending on the size and thickness of the leaves and the amount being processed.

Most common fixing methods

- Pan Firing: where tea leaves are heated in a large metal pan or wok that is heated by gas or wood fire6

- Steaming: where steam is forced through the mass of tea leaves7

- Tumblers: where a heated tumbler is used to heat the leaves8

- Baking: where an oven type machine is used to heat the leaves9

Less common fixing methods

- Sun drying: where the heat of the sun denatures the enzymes in the leaf by dehydration

- Microwaving: where electromagnetic waves are used to quickly heat the leaves, seen more in commercial applications

- Plunging in boiling water: where tea leaves are literally plunged into boiling water

When oxidation is prevented altogether, the catechins are left largely intact. The tea leaves keep their green color and vegetal characteristics. Think of an apple: once it is sliced open it quickly turns brown, but the apples in apple pie are not brown.

This is because the heat used to bake the pie denatured the polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase in the apples and prevented enzymatic browning. The same browning effect takes place in potatoes, avocados, bananas, etc.

When a semi-oxidized tea is being produced, some catechins convert to theaflavins and thearubigins, resulting in a slight browning usually along the edges of the leaves and yellower liquor. Lipids, amino acids, and carotenoids also begin to break down into flavor and aroma compounds.

When oxidation is allowed to run its course, the leaves exhibit an aroma and taste profile completely unrecognizable from a finished tea that was exempted from oxidation.

Theaflavins and thearubigins will now outnumber catechins, resulting in a brisk tasting tea with a reddish color in the cup. The chlorophylls will have been converted to pheophytins and pheophorbides, turning the leaves a coppery brown, and a myriad of new volatiles will have developed. In this case, the leaves are often just dried to halt any still-occurring reactions and to bring the tea to a shelf-stable moisture level.

This is a bit of a grey area in tea processing because here, drying can be considered a form of fixing. Heat is being used and oxidation is being halted. This is a great example of why it is sometimes important to view tea processing as more of a continuum rather than as a distinct set of steps. Regardless, there’s more to drying we need to look into.

Notes and Sources:

- Specifically when polyphenols in the cell’s vacuoles and the peroxidase in the cell’s peroxisomes mix with polyphenol oxidase in the cell’s cytoplasm. From Michael Harney’s 2008, “The Harney and Sons Guide to Tea.”

- In Latin, flavus means yellow.

- In Latin, rubugin means red.

- R.P. Basu and M.R. Ullah, “Notes on Tea Fermentation,” Two and a Bud 25, 1 (1978), 7–11.

- In semi-oxidized teas, specifically wulongs, a common descriptor used is “percentage of oxidation.” In most cases, this will be an estimated percentage unless the tea is produced on a commodity scale where chemical tests are performed to reveal the actual percentage of oxidation by way of catechin or theaflavin and thearubigin content.

- In China, this is referred to as chao qing (炒青), literally, “firing the green.”

- In China, this is referred to as zheng qing (蒸青), literally, “steam green.”

- In China, this is referred to as sha qing ji (杀青机), literally, “kill green machine.”

- In China, this is referred to as hong qing (烘青), literally, “baked green”